Jeter's Real Gift

The New York Times

September 19, 2014

by Doug Glanville

During the chaos and excitement of awaiting our firstborn child, my wife and I were decorating the nursery. Our son was due to arrive in late June of 2008 and we planned to put his crib in a baseball-themed room. So, in a rare act of handiwork, I tapped my inner do-it-yourself to paint the vaulted ceiling, and helped my wife pinstripe the walls.

When it came time to adorn those walls, we splashed them with old Glanville jerseys mixed in with some historical baseball artifacts, and then my wife’s designer eye determined that there was a void in a vertical section. We needed a bat.

I had played almost 15 years professionally, and I made sure that I collected memorabilia in my final few seasons. Cal Ripken Jr.’s spikes, a ball signed by the newly minted Hall of Famer Tom Glavine, my longtime teammate Sammy Sosa’s bat and items that were more personal, like an autographed bat from the man I was traded for in 1997, Mickey Morandini.

So I had quite a few bats. But when I went to look for the perfect one for the room, it dawned on me that my time with the Yankees in 2005 presented a void in my collectibles. That year I had spring training as a teammate of Jason Giambi, Gary Sheffield, A-Rod … and, of course, Derek Jeter.

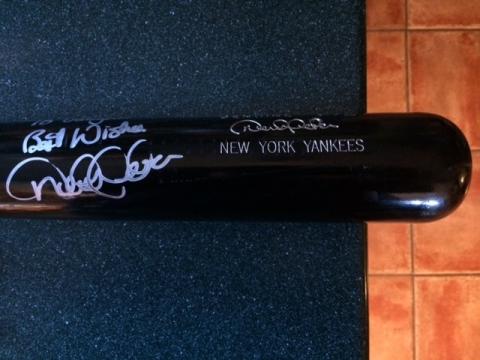

Given the performance-enhancing drugs cloud hovering over the game, I knew there was only one thing to do. Text Jeter. I asked him if he would sign a bat to my son, and send it to my home in Chicago. He replied in the affirmative.

The next morning, a box was on my doorstep. He had overnighted it.

His career, however, did not happen overnight. He scrapped, he battled, he fielded his way around the performance-enhancing drugs standard that began to expect even shortstops to hit 30 home runs a season. He said little, spoke with his bat, and toppled his opponents through sheer consistency.

As a center fielder, I found him extremely difficult to defend against. He was like Andre Agassi or any great tennis player who can wait until the last possible moment and then hit a ball in any direction. His “inside-out” signature swing neutralized your ability to get a good jump on the ball. He could hit a pitch to left field, then three innings later hit that same pitch down the right-field line. A master of disguise. Just as you never knew when he was sweating, you could never tell what he was going to do with the ball, and so you spent your defensive life flat-footed against Derek Jeter.

That was his game, and soon his body of work will be over, to be interpreted and picked apart in historical context till eternity. But even though baseball is in love with numbers, numbers don’t really tell you what he meant.

My son wasn’t yet born when the bat was signed for him, but Jeter’s signature endorsed his future, personalized as if he were a sure arrival. In a way, Jeter has been a father to the youth of baseball, even as he lived the life of a bachelor. He set an indelible example of how to approach the game with calm, focus, confidence and purpose. He ran every ball out, knowing that one at-bat can change the trajectory of a career. He understood (much as Satchel Paige did) that someone is always gaining on you, even if that someone is time. In many ways, he made a father’s job a lot easier by performing with excellence. The kind of excellence that allowed me, and countless other parents, to point to him and say, “Even when you achieve greatness, it is important how you have done so.”

While Jeter was hitting his way into Monument Park, my son kept growing. Whenever I called a Yankee game for ESPN, where I am an analyst, I would see Derek on the field and update him on my family. It was my way of thanking him for that grand gesture years ago. This season, I was able to tell him that my son was playing baseball and was a left-handed hitting and throwing ballplayer. I showed him pictures of my now three kids to demonstrate how gifts can be paid forward.

Not long ago, after I had watched Derek Jeter Day on TV, my son lay in bed and I told him that baseball had just honored a great player, one I’d played with and against, one who I hoped he would always remember had signed a bat for him. He told me that hearing about the celebration of Jeter’s career inspired him to play baseball when he grew up. He then asked me how many home runs I had hit. I told him 59.

“Wow! That is a lot of home runs.”

“Not really, the record-holder has over 700.”

Of course, 700 sounded like 18 million to him, so he was quiet for a while, as if I’d lost some sort of competition. I filled in the silence by explaining why Jeter was so special. I told him that he wasn’t a big home run hitter either, but he beat everyone by working hard, getting hits, hustling, rising to challenges during the most important games, and most important, playing without performance-enhancing drugs.

Then I realized that the fact that 700 sounded like 18 million to him was a gift. While my son is highly competitive, he still values what cannot be counted; his understanding is still open to the qualitative. Whether Jeter had 3,500 hits or 28,700 did not matter to him, only that Jeter was great, that he respected people and the game, cared about his father and found unforgettable ways to win with honor.

It is telling when you are forced to explain to a child the significance of a baseball career — or a life — without being able to use numbers to make your case. Some of the greatest players, stripped of their numbers, leave you little with which to work. But Derek Jeter still gives me plenty to say and, I get the sense, always will.

Republished from NYTimes.com

Photo Credit: Doug Glanville