Dream to Nightmare

The New York Times

June 29, 2012

By Doug Glanville

The College World Series wrapped up on Monday and the Arizona Wildcats were crowned college baseball’s national champions. Despite the elite talent of the participants in the series, many of the graduating seniors will move on to new lives without baseball. Only a select few can make a profession out of the game, and they will have a new set of expectations for themselves — and from their future baseball employers — once they sign on that dotted line.

Within that select group are the first-rounders, highly touted and the closest to a sure thing when it comes to forecasting the trajectory of a player on his drive to the major leagues. Most signees feel as if they are still dreaming, but first-rounders can hear the rhythmic ticking of the alarm clock of inevitability. They will get there. Only time stands in the way. They are that good.

After nearly five decades of draft history, the data is in. It is clear that most major league teams are assembled from high draft picks, the best of amateur baseball. The closer you are chosen to the first round, the better your odds of making it. In fact, first-rounders make it about 65 percent of the time, whereas those drafted in the 16th to 20th rounds have a 6.5 percent chance. That’s 10 times less likely.

The reason is talent, for sure, but also opportunity and investment. These amateur players have benefited from both, because when talented people receive more consistent expert education, they gain exponential advantage.

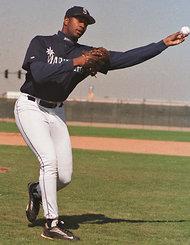

In 1991, I was one of those first-rounders. The Chicago Cubs chose me 12th overall after my junior year at the University of Pennsylvania, and I was on my way. But that same year, the player picked over everyone on earth, by the New York Yankees, was Brien Taylor. He was a North Carolina high schooler who looked as if he was pitching against toddlers.

Taylor, a left-hander, flirted with 100 m.p.h. He had gravity-defying secondary pitches that were still raw and unrefined, but were already on their way to inspiring the awe of his fastball. During negotiations, he made headlines because his mother acted as his lead agent, dispelling the idea that his family would know nothing about the negotiating game, nor have the desire to learn. Her hard-line stance trumped the stereotype that Taylor — a poor African-American from Beaufort, N.C. — would jump at the first offer to save his family. In the end, Taylor, with his family and, later, his new agent Scott Boras, would sign for $1.55 million. More than five times the Yankees’ original offer.

In his first two seasons, he did not disappoint. He baffled professional hitters in the minor leagues just as he had high-schoolers. But one day, while trying to protect his older brother from being bullied by a man in a North Carolina trailer park, Taylor ended up hurting his pitching shoulder. The damage was so severe that the legendary baseball shoulder physician Frank Jobe said it was one of the worst injuries he had ever seen.

After extensive rehabilitation, Taylor did make a return to the mound after missing an entire year, but he was not the same. He was hittable. He did not have the stuff that had made him the most dominant high school pitcher in decades. His career fizzled out eight years after he was drafted. The Yankees let him go in 1999 and two other teams gave him brief looks before deciding that he no longer had a future in the game.

He returned to North Carolina. The money was gone, so he had to take odd jobs, one of which was partnering with his father in his bricklaying work, to support a family that now included children of his own.

Earlier this month, Taylor was indicted on federal drug charges, including three counts of distributing crack cocaine. This stemmed from an arrest in March after he had been accused of selling directly to an agent. Now he is facing a new kind of inevitability — not one having to do with major league stardom, but one that makes a jail sentence a mere formality. He is 40, a shell of the person he was on draft day.

This isn’t supposed to be the storyline. The dream does not end in handcuffs before it even starts. Taylor never threw a pitch in Yankee Stadium. He never threw eight brilliant innings and then got to hand the ball over to Mariano Rivera. He wasn’t there for Jeter’s 3,000th hit, and he missed the Yankees’ first World Series title in nine years when they won in 2009.

In that trailer park, Taylor did what anyone would have done for a brother who was being threatened. Sure, he should have fought with his non-pitching hand, or tried to be the negotiator, but such things are not always options in that split second it takes for life to change. The kind of thing that happened to him could have happened to anyone.

Meanwhile, here I was, 11 picks after Taylor, able to get my time in the big leagues. I made my major league debut, earned a multiyear deal, had a locker next to Alex Rodriguez’s. I try to tell myself that it was because of my better judgment about what risks to take, or my Ivy League opportunities, but comfort does not come. For me, reading about Brien Taylor is haunting.

All this points to the illusion of inevitability. You can engineer the perfect diet and workout routine, be a good citizen and work at your craft year-round, and still have your dream destroyed by something out of your control. It could even happen while you’re doing what you wholeheartedly believe is right.

A career in sports is only a flash in time, whether it’s a 15-season run or a 15-day run. When it all finally ends, you have to face yourself — it’s as if you are both on the mound and in the batter’s box. And it’s a standstill. Then, the reality that you cannot play anymore shocks you back to life. You hope you have saved enough money, you hope divorce doesn’t await you; you certainly don’t expect that a jail cell door might close on your freedom.

I guess I don’t see a big difference between Brien Taylor and me, or Brien Taylor and any of those other players chosen at the top of the draft. Every player, whenever he stops playing and for whatever reason, feels the same thing, because we’ve all been living a passion whose only true inevitability is that it will end. Sadly, with Taylor, you feel like he never got started. His career seemed to be forever pointed behind him, to one sliver in time that changed everything. And now it appears that he may have nothing but time, stuck in a future that keeps him in that same tormenting past.

Republished from The New York Times

Photo Credit: Lenny Ignelzi/Associated Press